Laws & Policies

Please Note:

Many of these sections are condensed versions of Wabaseemoong Independent Nations Codes, for easier comprehension. To read these policies in full, go to the Resource Library page of the website.

The Rights of the Anishinaabe Child

The concept of child welfare, including customary care and custom adoption, has always been an important aspect of Indigenous life, and predates any legislation or system. The goals have always been the safety and security of our children, which is parallel to the current welfare approach of protection and permanency.

Programs of the past have asserted traditional laws and approaches to family well-being, but they did not acknowledge the sacred rights of the child.

The Rights of the Anishinaabe Child are crucial in the development of personal identity. Other components include a sense of continuity and belonging, and uniqueness from others. Identity can be affected by our genetics, culture, loved ones, experiences and choices.

In Anishinaabe tradition, infants and children are raised the same until they reach adolescence, at which point they receive gendered roles and responsibilities. At this stage, the soul (ojijaak) and body (weo) are joined with the mind (nidibaan) through rites of passage, and identity formation is considered complete.

Of course, this sacred unification is disrupted by the child welfare system.

Since 2016, child protection workers have been legally obligated to review these rights and also have the child in each case review and sign off, as is possible, on their understanding of these rights.

Under the Great Law of the Anishinabeg, an Anishinaabe child has 13 rights, just as there are 13 patterns on the shell of the snapping turtle.

All children have the right to:

- their name anishinaabe ishinikasoowin

- their clan dodem

- be with family gutsiimug

- cultural and ceremonial practices anishinaabe miiniggisiwin

- their identity anishinabewin

- their language anishinabemoowin

- a purposeful and zestful life mino bimatiziwin

- their ancestral land anishinaabe akiing

- the lifestyle of the anishinaabe anishinabechigewin

- good education kinamaatiwin

- protection within the family shanawentasoowin

- protection outside the family ganawentasoowin

This is a condensed version of Lawrence W. Jourdain’s research and interpretation. Read his original document in full.

Understanding our New Self-governed Child Welfare Authority

Wabashki Maakinaakoons is a alternative model of child care. It will restore and emphasize traditional family welfare practices, provide decolonized, anti-oppressive healing through culturally grounded values and connection.

The WCWA approach creates layers of protection for families and holds a space for their voices. Accountability is required from all parties, and independent bodies are available for advocacy.

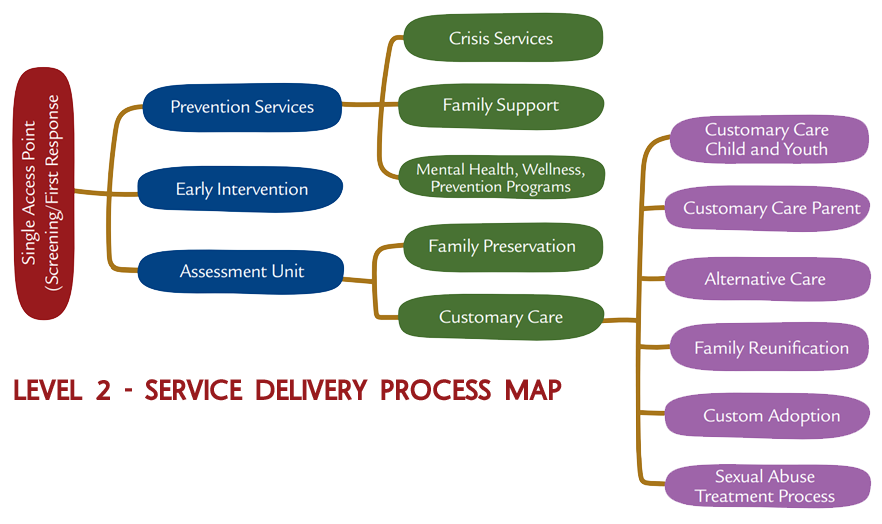

When a child is identified as “at risk of harm”, the WCWA assessment unit completes its study within five days, with input from family members. It may recommend enrollment into one of the following streams:

- Prevention Services supports long-term, sustainable, positive change in Wabaseemoong. It includes crisis support, family support, mental health & wellness, family and youth programming.

- Early Intervention is for families in which there are risks that could affect the safety of the children, but would not warrant a formal assessment or investigation. To be eligible for this service, families must be willing and able to collaborate with workers. An example would be a gambling addiction in which guardians are leaving children inadequately supervised.

- Family Preservation is required when a child’s safety risk or the breakdown of the family has been confirmed. This program provides immediate, intensive support for 3-8 weeks. It may include coordination with other services, individual and family counselling, cultural interventions and aftercare planning and follow-up.

- Customary Care involves children facing an immediate threat who are placed under emergency care or safe home declaration for up to 10 days during assessment. One of five orders (Shawentassowin, Ganwentassowin, Obigiasoowin, Gagiigimassowin, Nabiigundiwin) will be selected with input from the family and sanctioned by the Wiidokazawad Committee. Children’s voices must be heard in this process. Parents in the Customary Care stream are assigned a worker who helps them to meet the requirements of their family service plan.

- Family reunification, when safe, is always the goal for every WFMS child and parent.

There are additional safeguards in place for children and their families in the Wabashki Maakinaakoons Family System.

- All WCWA employees will receive a core curriculum of Wabaseemoong cultural teachings, including local family history, clan systems, community legends, spiritual guardians and sacred sites.

- Employees will be honest about their own struggles and histories, and work with humility and compassion. They will be at risk of burnout in their high-stress positions, and will keep their self-care a priority. Managers will pursue ongoing development to increase emotional intelligence, conflict resolution and effective management.

- The Onakonigewad ensures Abinoojii Inakonigewin is carried out properly. It reviews, oversees and amends the Wabaseemoong Customary Codes, and its policies and manuals, as required.

- The Wabashki Maakinaakoons Board oversees the WCWA organization, and receives its monthly reports. The Board approves budgets, and system and personnel changes, by resolution.

- The Family Advocate works independently of WCWA and is available for families who need support in navigating the system, and in situations where young people believe their rights have been violated.

- The Onakonigewad Review Board is available for families and children to voice their concerns and to appeal decisions if they are not satisfied with the actions of WCWA.

Turning Our Child Care Teachings into Law

As of January 2021, Wabaseemoong Independent Nations has gained control of its Child and Family Services, which means the ultimate responsibility of raising our children has legally returned to our parents, families and community.

To ensure the WIN self-governing child care code meets its legal responsibilities, and at the same time, maintains traditional ways of guiding our children, governing principles must be interpreted, recorded, and passed as laws.

This is a process of exploring and understanding our past, even though it is difficult, so that we can determine our future.

There have been many traumatic events in our history that have created difficulties in caring for our children. They include residential schools; the Northern Adoption Project; hydro-electrical developments with its flooding, forced relocation and lost livelihoods; addictions; loss of traditional practices, values & beliefs; and Children’s Aid Society (CAS) intrusions including systematic removal of children from our families and communities.

Over the years, Wabaseemoong Independent Nations has attempted to break these cycles with various governments, organizations and corporations, but all the while, our children were removed from our homes. Finally, in 1990, WIN reached a turning point when Chief and Council blocked the reserve line to prevent CAS from entering the community. This put us on the path to self-governance in childcare.

Process of creating Abinoojii Inakonigewin (Treaty 3 Child Care Law)

- The Millenium Resolution was declared in 2000. Shortly after, women called for a law that would specifically care for our children.

- Information was received from the Governance Initiative and a drafting team was formed.

- Elders drafted instructions, which were then reviewed.

- Ceremonies were performed in the beginning, during and after the finalization process.

- In 2005, the National Assembly endorsed and passed this law.

Process of creating Wabaseemoong Independent Nations Customary Care Code

- After Abinoojii Inakonigewin was passed at the National Assembly, Mootsitisin

- A document was drafted, based on knowledge of our Elders and wishes of the WIN people.

- The document was reviewed by all interest groups and was agreed upon.

- Elders were approached for guidance and they recommended seeking guidance through ceremony.

- The Shaking Tent gave key messages, which were incorporated into the document.

- The WIN Customary Care Code was signed into effect in 2017.

Anishinaabe Laws existed before contact and before Treaties

They are sacred, traditional and customary, and they are not extinguished by Treaties.

The source of Anishinaabe Laws is Miinigo`iziwin. Sacred Law and Traditional Law cannot be written, but Customary Law may be written with the guidance, direction and permission of the Elders through ceremonies.

The Well-being of Our Children: A Timeline

Since time immemorial, our children lived happy lives on the land. They received Elders’ teachings about our traditions so they could use the gifts of the waters, lands and animals with respect. They learned to trap, fish, garden and pick medicine. They travelled with their families, according to the seasons, to pick rice and blueberries. They had deep connections to their families and their surroundings.